|

Why does history matter? Either you already know why, or you don’t care. So no matter which of those describes you, you're not likely to feel much compulsion to follow that headline which means that nobody is likely to land at my blog, which basically sums up my entire online-platform-building strategy.

However, at the risk of alienating hypothetical readers whom I imagine have come this far, let me say that I intend to demonstrate one single, all-important fact: the older a bit of history is, the more it matters. That idea flies in the face of our modern thinking. We tend to attach more importance to things which are taking place right now, and we feel ambivalent toward any event which happened before our lifetime. In fact, the further back in time it is, the less we tend to care about it. But if my main point is true, then the habit we have of reading history only occasionally (if it entertains us) while we gobble up tons of information about the present is actually not only backwards, but counter-productive to the point of absurdity. In reality, it should be the other way round: We should know lots and lots about history from every era, even at the expense of paying attention to the present horror of ‘current events’, many of which are not really that current, and many of which barely qualify as ‘events’. I begin with a concept which may have come from the study of physics, which I would know for sure if I were a physicist or if I could be troubled to look it up online. It’s a concept which many people know well enough to serve us for this discussion – the butterfly effect. The butterfly effect is shorthand for a small event which has enormous consequences because of a series of exponential results. An example goes like this: Suppose you wanted to figure out what the weather would do a year from now. With all the computers on earth, we should be able to, right? Well actually, no, because there are too many variables. Let’s say you managed to put every single weather factor into the world’s computers; wind, temperature, pollution, moisture level, number of people breathing out carbon dioxide, number of new trees breathing out oxygen... everything. But you missed a single butterfly in Singapore. That butterfly flaps its wings, which doesn’t do much at first; it just creates little eddies in the air above its flower. But now, the air directly above the butterfly is moving in a way you didn’t predict. That creates a little bubble of uncertainty which causes the air passing over that garden to move in a way you didn’t expect. Now that breeze is carrying new, unforeseen gusts with it, and because they were unforeseen, they impact the winds which pass over Singapore in ways you could not have quite gotten right. The breeze is picked up by currents of air moving over the South China Sea, which are now heavier by just a little, and drifting more than we thought they would. Suddenly the rising moisture from the ocean’s surface has a more dynamic atmosphere to contend with: fresh currents emerge as a result; patterns collide and stretch; new possibilities multiply every second. Before you know it, a simple gust which had been slowly picking up momentum now turns into a more forceful gale, and, turning in on itself, starts to cascade as it swirls. A seasonal storm finds unexpected energy, then meets a cool front, and suddenly what would have been a windstorm is more powerful than anyone anticipated. A hurricane is born. Entire mainland villages lie in its path, and hundreds are left homeless. All because of a butterfly. This illustration of the butterfly has become common coin for many people, so much so that it’s now almost a trope for time-travel stories. But its real value is in helping us understand how every single historical event has implications over time. In fact, as with the butterfly, so with history; the older an event is in time, the more impact it has on subsequent events. Here’s a real-life demonstration... Christopher Columbus sailed west. He did so for specific reasons and on behalf of certain financial backers. The immediate impact was felt within a very small circle of people. Ferdinand and Isabella started to plan further expeditions, Columbus tried to demonstrate that he’d proven his theories, and certain indigenous Americans became aware that they were not alone. Those were momentous consequences, but they were nothing compared to the larger consequences which followed the next year, and the year after that, and the year after that. In fact, the more time you give it, the more astounding the effects of Columbus’ journey become. Native Americans were exposed to diseases for which they had no immunity; Spain received an unparalleled influx of precious metals which led to them overextending their spending which led to more than half a dozen bankruptcies while they were still the predominant world power; more land in the Americas led to plantations becoming increasingly important, which required more manpower, which fed the African slave trade; which presaged Britain’s naval dominion of the ocean trade routes, which made them the next great superpower; which allowed the formation of American colonies which eventually declared independence; which continued to feed the slave trade, which increased public resistance to human slavery on the new continent, which created conflict, which led to a bloody war, which allowed people to take advantage of the depleted south, which created racist counter-reactions, which made an environment ripe for civil rights... and on and on it goes. None of which – not one thing – would have happened the same way if Columbus hadn’t happened. The further away from Columbus we get, the more his actions impact the world of today. The same thing is true of every story in your old history textbooks. The further back in time an event occurred, the more impact it has made on the world, and on your life. Stuff which happened yesterday? Well, the effects of those things take time. They may impact the future, but for us they are still only echoes of the past. The practical upshot of this principle is something like this: The more you know about history, the more you understand the present. The less you know about history, the less the present will make sense – or the right kind of sense – as you try to navigate a world which has arguably been made worse by the ubiquity of instant news. So, for everyone who’s read this far, I offer a couple observations. If you already value history, now you have another way to explain to other people why history matters, and why they should care. If you don’t like history (first of all, why are you still reading? but more importantly) I hope that you know now why so many people repeat the old phrase about how those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it. It’s because history isn’t a bunch of stuff that happened before, to other people. It’s a bunch of stuff that’s still happening; and it’s happening to us right now.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

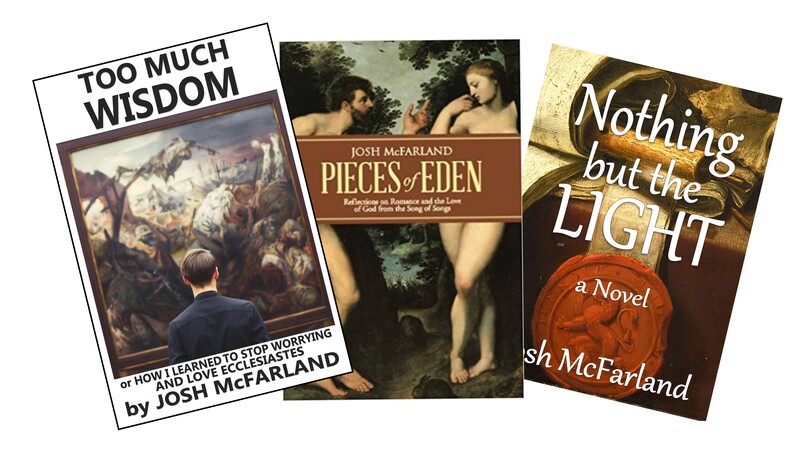

Click on the link to go right to Josh's Amazon Author page.www.amazon.com/Josh-McFarland/e/B0868TJ4CP/ref=dp_byline_cont_book_1 Archives

February 2021

Categories |

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by Hostgator

RSS Feed

RSS Feed